The Case of American Exceptionalism - Part 8

- Soham Mukherjee

- Nov 3, 2018

- 3 min read

-Brian Proferes Member (MCG)

Throughout this series we have explored the rise and fall of productivity and have seen that the factors were a mix of inevitable change and policy decisions. In Part 1 of our Conclusion installment we will look towards the future and ask if there is promising growth ahead.

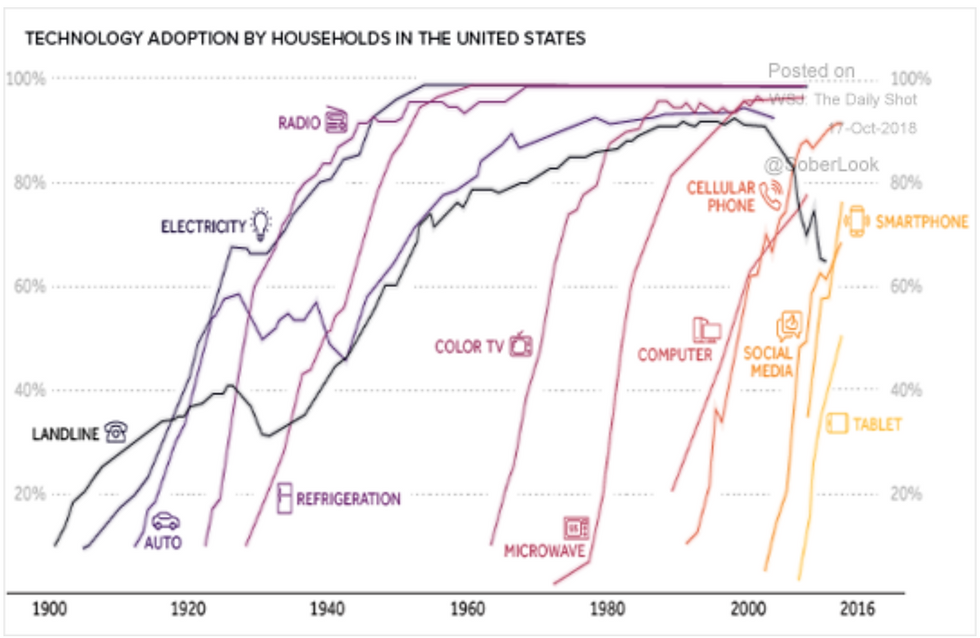

Recall from an earlier paper we determined that productivity growth, and ultimately gains in standard of living, come from technological progress. In particular we described how the emergence of a new technology usually takes on a logistic path as the effective implementation of a new technology occurs over a relatively short period of time. This following graph from the Wall Street Journal shows how different technologies have emerged over the last century. The paths reaffirm our belief of logistic growth.

This graph is another piece of evidence that the productivity miracle was in part a result of revolutionary technologies coming together during one short time interval. There is a big gap in meaningful innovations entering society from 1970 to 1990; this graph obviously omits many technologies but those shown reflect the most meaningful developments. Similarly, the decade beginning in 1994 coincides with the sharp rise of phones and computers, but once those technologies were fully integrated productivity inevitably slowed down.

It is important we recognize how perspective determines the way we view technology: We can either say “productivity fell off once all of these technologies or adopted” or “these technologies caused productivity to reach levels that are typically unseen or unsustainable”. If we look at technological revolutions as the norm rather than the exception then we are vulnerable to disappointment as one technological advances of extraordinary magnitude are very rare.

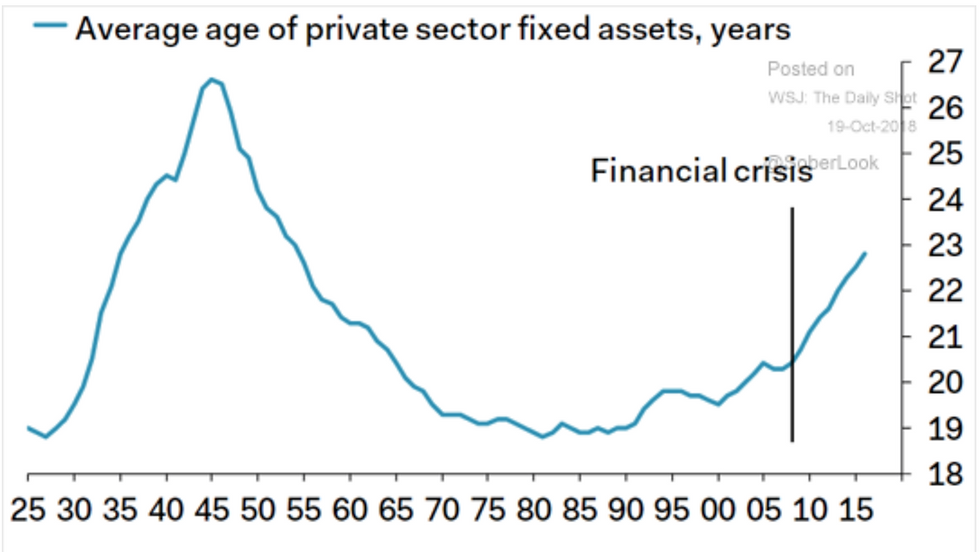

To get another glance into the rarity of technological advances, here is a graph showing the average age of private sector fixed assets over the last century. In other words, how modern or new is the relative machinery being used; times of great technological progress should bring about new machines that are more efficient than their older analogs.

It is evident that World War II and the ensuing economic boom resulted in a lower age of fixed assets as the new technologies implemented were significantly more productive than those that existed before the war. Yet over the past few decades the age has increased, reflecting the lack of a technological boom that could produce newer machines; there was a short period from 1994-2004 where new machines emerged, but otherwise our capital composition has not significantly changed. | If the age of our capital is increasing it means we are essentially using the same machinery, which of course will not encourage increases in productivity.

The obvious conclusion here is that to return to great levels of growth we must realize great gains in technology that will in theory boost wages and the overall standard of living. The government should enact policies that facilitate the great innovation engine. Growth in technology is still remarkable but there are not many advancements made that impact the realm of day to day life. Artificial Intelligence is likely the future as we will develop machines that can think in increasingly sophisticated manners. Eventually these advanced technologies should trickle into everyday life but until then it is hard to visualize any dramatic advances coming in the near future.

Nobody can predict the future; people in 1970 probably could never imagine the world that exists today, so it is not appropriate to say the future will hold slow growth. Fifty years from now we will (hopefully) have technology we could have never dreamed of today. Whether or not those technologies are luxury items or day to day devices that impact our productivity will ultimately define the long run health of the economy.

What is most important is that America remains the vanguard when it comes to innovation and technological progress. Other countries are gaining ground but that should be encouraging: the more brilliant minds there are to work on an issue, the more likely meaningful innovations will result for all to use.

In the second part of our conclusion we will finish up by looking at what I consider to be the most significant issue facing our country today.

Comments