The case of American exceptionalism - Part 5

- Soham Mukherjee

- Sep 12, 2018

- 6 min read

In the last installment we examined how technological gains have fizzled out since 1970 and declared the decline to a degree inevitable due to the fact that revolutionary leaps in productivity are simply unsustainable. Our next step in investigating why American Growth has stalled will be to explain the growth in wealth inequality. Why has the 1% progressed so astonishingly far compared to the rest of the population? Real wage growth has been non-existent since 1970; we discussed earlier how a “Great Compression” helped stimulate one of the healthiest middle classes in world history, so what happened?

The graph, which shows the income of the top percentiles as a fraction of total income, reaffirms our discussion of the “Great Compression” that occurred from 1940 to 1970 and illustrates how inequality has since been on an upward trend to levels not seen since the peak of the Roarin’ 20s. Our goal is to find out what caused the historic slump in inequality during the middle of the century and determine if those factors were a one-time miracle or something that policy could recreate

We are going to continue using ideas from Robert Gordon’s Rise and Fall of American Growth while also incorporating concepts from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty First Century. The latter is a spectacular, albeit extremely lengthy, book that all business students would benefit from reading. We will cover some of the major ideas in this paper.

Let’s start by making a reasonable assumption: wealth comes from either income from labor or income from capital. If an individual makes money we are going to assume it is either from his labor or the return generated by capital (think financial assets like stocks and bonds or real estate; broadly speaking capital is any “non-human asset that can be owned and exchanged on some market” (Piketty)). We are going to look separately at income inequality from labor and capital, as each paints a different portrait.

Inequality in Labor Income:

One of the major developments in the labor market over the past half century has been the emergence of a “Superstar Economy” where vast sums are paid to figures who hold the greatest influence and power in their respective fields. Whether it is CEOs or other high-ranking officials in a company or athletes or actors, salaries for those at the top have skyrocketed while the middle and lower class have seen stagnant real wages.

Traditional economic theory states that a worker should be paid her marginal product of labor, so our first guess would be to suppose that those at the top of corporation have done a better job earning profits for their companies and thus should be appropriately rewarded. But research has shown that in many cases this is patently untrue and there are many instances where executives are paid enormous sums despite driving the company into distress. Furthermore, there is little evidence that paying an executive like a superstar has lead them to be more productive. If these executives haven’t been more productive workers, why are they getting paid like superstars?

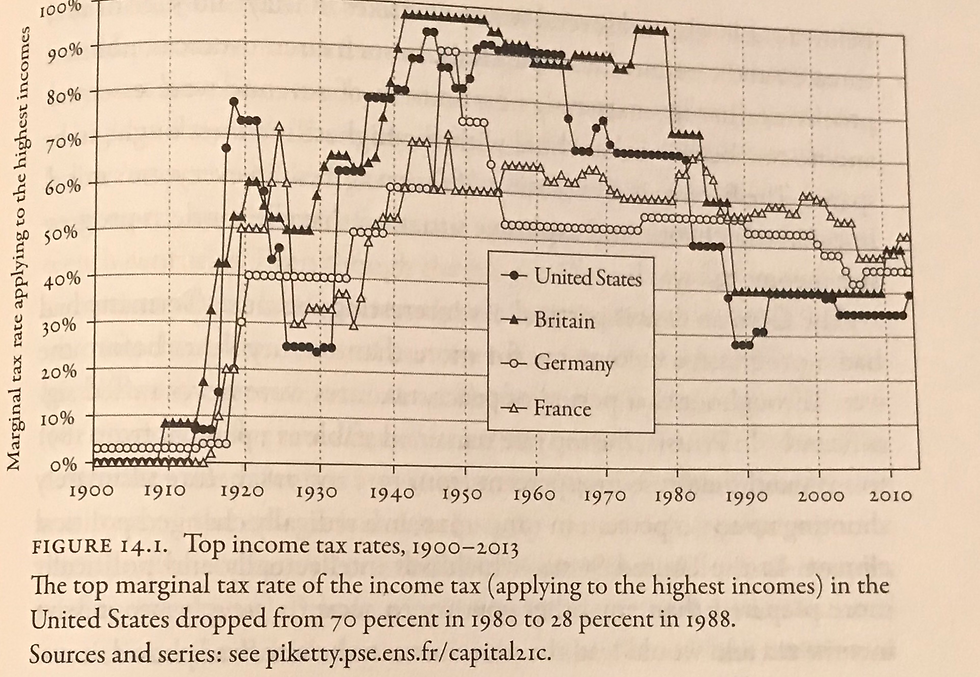

Let’s start by looking at top tax rates in the United States over the last hundred plus years.

The United States for a long time maintained one of the highest top tax rates compared to other developed nations, but rates started falling around 1980 and have stayed low in the last few decades. We recall our earlier graph of inequality and see that there appears to be a strong correlation between the level of wealth held by the top percentage as well as the top tax rate.

At first glance this will seem obvious, lower taxes clearly means more wealth, but let’s take a step back and think a little deeper. Those who advance the notion of “Trickle-Down Economics” will tell you that taxing the rich less will allow wealth to diffuse through the economy and help the middle and lower classes, but our graphs show that is far from the case.

One of the main reasons behind the tax cuts was a fear among politicians that other countries were “catching up” to the United States, and to maintain the lead position in global wealth the country needed to cut taxes to become more competitive. This conservative thinking is misguided because those countries who were “catching up” were merely making the inevitable advances that resurrected them from the destruction of World War II. Remember the lead the United States gained over the rest of the world was more out of luck than genuine ability, so worrying about losing a lead you never should’ve had is a recipe for messing with economic dynamics.

Let’s look at the tax cut situation from the perspective of an executive. The modern American economy is generally considered to have begun post-World War II so the development of corporate America was largely under a very high top tax rate, meaning there was little incentive for an executive to lobby for a higher wage since he would lose much of those gains to taxes. However once top tax rates, fell, executives had more incentive to work for a higher wage because less of it would be lost to taxes. Thus executives wanted to take more of the pie for themselves and away from other workers.

So how does an executive manage to convince others to pay him such outrageous amounts of money? Consider the Marginal Productivity argument we advanced earlier: if you are a worker whose job is to simply produce goods or services, it is easy to put a number on how much revenue you generate. Thus lower level jobs tend to have better defined marginal productivities and can thus be paid more “accurately”. But what about the marginal productivity of a CEO? It’s much harder to find concrete evidence of how much revenue the actions of CEO help generate, and it is very easy to ascribe her credit when it may have been other variables lifting the company to new heights. So when a CEO’s pay is determined, it is much easier to defend higher salaries, for anyone could cite “vast oversight that assists the company in a myriad of ways that can’t be quantified”. Consider who determines the salary of a high-ranking executive. More often than not it is the board of directors who determine the pay of the CEO, but many of those directors are also officials who will similarly depend on a board of their own to determine their pay package. Many executives will find themselves on several different boards, creating a situation where boards are interlocked:

Person A will be determining the salary of person B who will in turn determine the salary of person C who is determining the salary of person A. A “You help me and I’ll help out you” system inevitably emerges, and when asked to cite reasons for large payments, no one can argue against the poorly defined marginal productivity argument we discussed above. So now that we have a foundation for the rise of the “Superstar Economy”, let’s try and find the culprit behind stagnant real wages among the middle and lower classes. Of course, executives taking a bigger chunk of the pie for themselves will leave less for the rest, but let’s try and explore alternative reasons. We have explored the drop in productivity since 1970, and if workers are paid their marginal product, then clearly wages will not rise if workers maintain the same levels of productivity; all gains in wages will simply be passed through to prices, wiping away all nominal gains. Productivity and wages go hand in hand so without technological progress it is unlikely workers will see their real income increase anytime soon.

Although the nominal minimum wage has steadily grown since its inception, the real minimum wage has actually been on a steady decline for years. The graph below compares the real and nominal minimum wage:

The real value peaked in the 1960s but starting in 1970 the wage began a downward trend. It is clear that the minimum wage should rise if it wants to reach its previous highs, but the many argue that raising the minimum wage would cause firms to hire fewer workers, since they are now paying more for each worker. But is that really true?

Introductory Microeconomic classes discuss how a price floor, which classifies the minimum wages, is effective if the equilibrium price is below the price floor. However, if the equilibrium is actually above the price floor, then there will be an inadvertent lowering of prices. Many economists below the competitive equilibrium wage rate is well above where the minimum wage is set, so thus raising it should not have detrimental impact on company’s profits. Globalization, or the inevitable catching up of other nations, has allowed the labor market to become more competitive and thus has encouraged companies to look for cheaper sources of labor outside the US. Unions have also seen their influence in the past few decades, providing workers less bargaining power to raise wages.

Ultimately the real wage stagnation question, like the productivity disappearance, has puzzled economists, and there is no definitive answer. All we know for sure is that inequality has widened significantly in the past several decades to levels not seen since the early 20th century. In our next installment we’ll look at how inequality in capital income has evolved and determine whether the emergence of inequality was a self-inflicted wound or simply a permanent complement to capitalism. - Brian Proferes (Member MCG)

Comments